On Ecology

Introduction to the Issue

We can glimpse the infinite on a clear, starry night, from an expansive viewpoint, or even nestled in the underbrush of a dense forest. When we slow down to examine the toil of an earthworm or snail, as they move through a common grassy patch, or even within a potted plant, we see the enormity and importance of a world that is easy to overlook. This opening up and experiencing of the world beyond us, or the slowing down and witnessing of the myriad worlds around us, can fundamentally reshape our consciousness. We “fit” differently into the world around us when we absorb and experience nature.

The humbling impact of understanding oneself as part of a greater whole can change how we think and how we treat others. The fact that nature fundamentally reshapes consciousness is increasingly informing contemporary approaches to wellness, leading therapeutic practitioners to recommend time in nature as a treatment for depression and anxiety. In the contemplative traditions, including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism, this altered sense of self in relation to nature goes beyond awe and inspiration. It is, in fact, rooted in ontological analyses of being that reveals the self as nature, nature as the self. In this issue of Tarka, we look at the intersection of ecology and contemplative practice - including various ways of understanding and relating to nature, environmental degradation, and modes for healing. The result is an interdisciplinary, multifaceted study of ecology. For example, Carryn Mills explores how a deep analysis of the Saṃkhyan concepts of prakṛti and puruṣa, commonly translated as matter and spirit, merges the notions of self and nature. Alternatively, Isa Gucciardi lifts up aspects of bodily experiences to consider how they connect the individual to the natural rhythms of life and the world all around. And, Martha Eddy employs the concept “childhoodnature,” to encourage a therapeutic, somatic return to innocence and to reject the idea that humans are superior to nature.

Ecology entails a recognition of interdependence, connection, and relationship. In scientific terms, it is the study of living organisms and the natural (living) environment. The health and wellbeing of one form of life is dependent upon the environment where it lives and the creatures that surround it. This is true within national parks and wilderness lands and also within cities and suburban developments. The connection between ecology and the contemplative traditions is perhaps best exemplified through the teachings on compassion and the Bodhisattva vow in Buddhism that delays personal enlightenment for the benefit of others. Interdependence, or, in Thich Nhat Han’s words, inter-being, is a spiritual, ecological worldview that emphasizes the many ways that every individual being is connected to everything else. Interdependence is specifically explored here in the excerpt from Stephanie Kaza’s book Green Buddhism, where she relates the teaching narrative of Indra’s infinitely intersecting net to contemplative practice. When the individual self is de-centered and interconnection is emphasized, care for the world around us takes on a different form.

The word nature refers to the natural land around us, as well as to our deepest sense of self. Yet, how nature is defined and understood popularly today is often rooted in mechanistic and materialistic assumptions about reality. Perhaps most commonly, it is considered an object other than us that must be either harnessed or protected. This perspective inadvertently feeds into a power imbalance wherein humans are given more agency and importance than the world they occupy. Like colonial and patriarchal systems, the power imbalance between human agency and nature has wide ranging consequences. In response, a number of articles in this issue, including authors Greta Gaard, Rebekah Nagy, and Jesse Jagtiani unpack and explore the philosophy of ecofeminism, a system that recognizes the destructive role of power imbalance and domination and proposes alternatives.

There is often a perceived divide between the concerns related to environmental justice and social justice. The possibility of jobs in the timber industry or coal (to name just two examples) is leveled against the concern for the environment. In this way, the early stages of environmental activism seemed to pit elite ideals (i.e. save the redwoods) against the practical concerns of lower-income families. We are gradually entering a new era where these concerns are shifting. The impact of environmental destruction disproportionately affects lower-income communities, who often lack the resources to move away from polluted land, who cannot afford or access clean, wholesome, and/or organic foods, and whose labor has often been replaced by machinery. Perhaps the issue never really was jobs versus the environment, but rather an economic system that values profit over ethics and certain lives more than others.

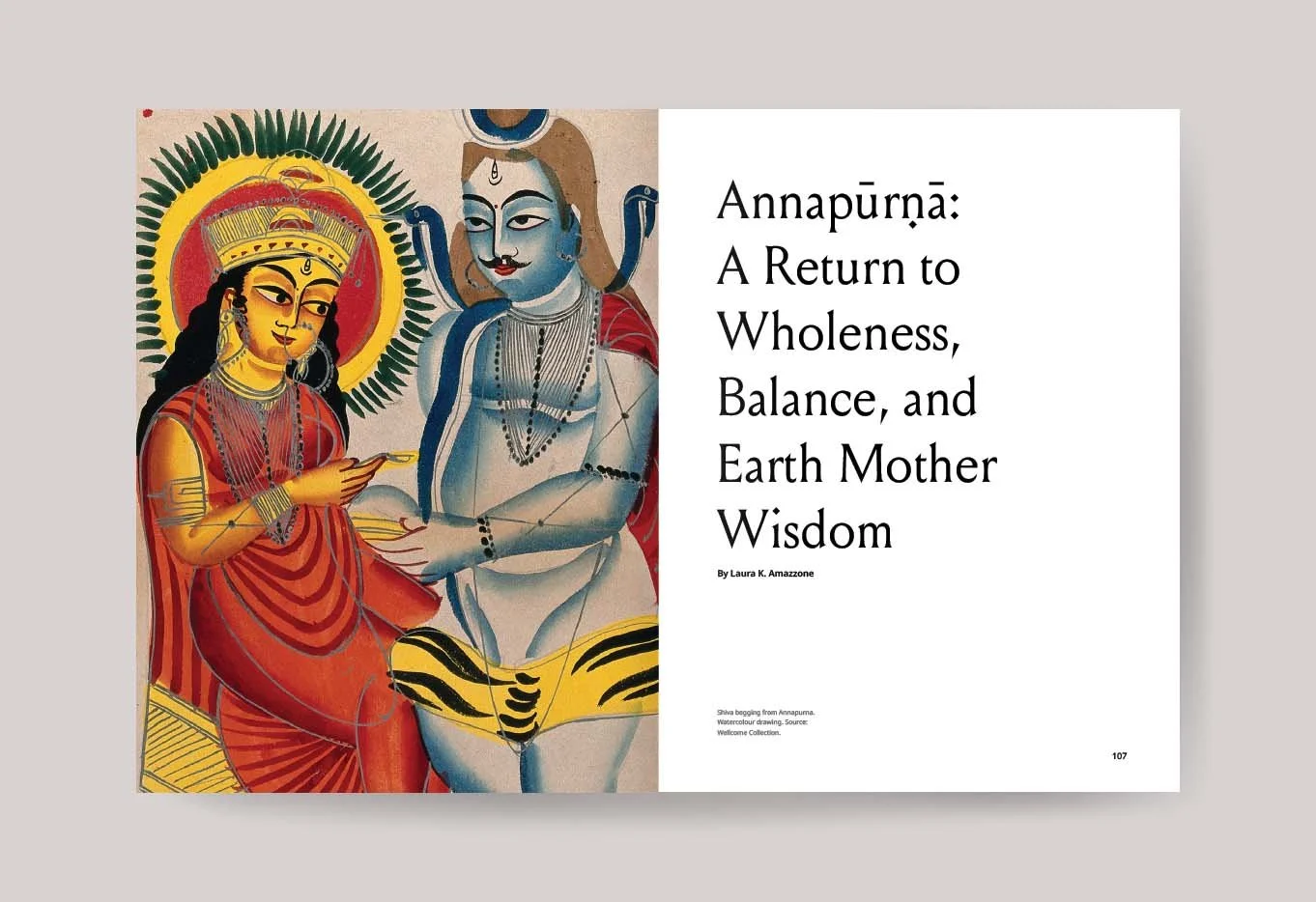

The era upon us is now being recognized as the Anthropocene, a term for the current geologic age in which human activity is the dominant cause of change and evolution for the climate and environment. Many scientists and activists report that we are at a tipping point and our collective habits of consumption, development, and the need for entertainment are irrevocably causing damage - to the natural world around and within each of us. Given how frequently contemplative teachings are interpreted (rightly or wrongly) in renunciant ways, the status of nature presents an ongoing dilemma. A renunciant, after all, is practicing to ultimately leave the world behind. Still, the world to be renounced (in the ascetic traditions) is most often the world of productivity, commerce, and materialism. As Christopher Key Chapple reminds us in his book Living Landscapes (paraphrasing from George James), “Nature is not the problem; human industrialization and the manipulation of nature are the problem.” Several authors in this issue consider aspects of landscape, ritual, and meditation as means to restoratively engage with nature. Katy Jane considers the Sacred Rivers of India. Laura Amazzone looks at resources from the Shakti (goddess) tradition and Annapurna (the Goddess of food and nourishment). Jean Gardner explores three, historic, urban soil communities and the possibility of creating a soil-generating community. Ramesh Bjonnes asks why yogis eat carrots instead of cows, and our practice section includes several impermanent earth art mandalas by artist Day Schildkret.

Protection of our natural spaces is a protection of home, for ourselves, for the wildlife, and for future generations. Perhaps, in addition to the critical work for environmental justice, including protests, policy changes, restoration projects, and the ongoing development of renewable energy, what is needed is the cultivation of an ecology of belonging, of seeing oneself as part of the greater whole - not separate, superior, or even in charge of protecting - but immersed into the great web of being. This sense of belonging might be what saves us - mentally, physically and spiritually - especially when the challenges appear insurmountable.

A child, fascinated by tadpoles, patiently sits at the edge of a seasonal waterway. The willingness to observe the details is a habit – or practice – that invites a different kind of belonging to nature. Shadows cast by larger leaves give temporary shelter to small frogs. Insects thrive in the dense surrounding grass. Spring rain gives home and habitat to a variety of wetland creatures. Summer flowers emerge from seeds in the retreating waterline. Autumn leaves then lay the groundwork for new soil that will mature over the winter months. The cycles of days, lunar months, and seasons shape the land and all that lives within and above it. Contemplative practice encourages quiet observation – of land, of passing thoughts, of suffering, and of joy. It will not remove plastic from the ocean, but it might inspire a future engineer or current scientist or activist with enough fortitude and clarity to make a difference.

— Stephanie Corigliano, Tarka Editor-in-Chief

Purchase Options

Digital